Introduction by Ira Dilworth

On 4 March 1930 (almost exactly 15 years before her death on 2 March 1945) Emily Carr made, as far as I know, her only formal public address.[A] The occasion was a meeting in the Crystal Garden of the Victoria Women’s Canadian Club—the meeting to celebrate Emily Carr’s first solo show in her native city.

There is plenty of evidence that the occasion was considered to be an important one. In spite of the fact that she was always scornful about “talk” in connection with painting, Miss Carr herself was very excited by the invitation to speak and took great pains in the preparation of her address—it survives in a perfectly “clean” typescript.

She was troubled during the preparation of the talk by the fact that her beloved monkey, Woo, was taken violently ill. While Emily was occupied with writing the address, Woo appropriated and devoured a tube of yellow paint, and, despite the efforts of a veterinary and everything Emily could do herself was in very serious condition. A day before the event Emily refused flatly to give the talk unless Woo was better, and indeed it was only a few hours before the time for the address that she finally agreed, Woo having taken a definite turn for the better. She has made an amusing and, at the same time, pathetic reference to this experience in “The Life of Woo.” Its closing sentences are: “The talk went over on the crest of such happy thanksgiving, it made a hit. The credit belonged to Woo’s tough constitution.”

Two days prior to the address the Victoria Daily Colonist carried an interesting article by Ludewyck Bosch, an artist and critic visiting in Victoria. He spoke of his amazement on first seeing the paintings of Emily Carr and of his astonishment that they were not better and more favourably known by Canadians. He also noted the fact that an exhibition was being held. He said: “We are really very glad to hear that through the medium of the Women’s Canadian Club an exhibition of Miss Carr’s work will be held at the Crystal Garden on March 4th. While this exhibition is for one day only we have no doubt that the Canadian government, which has already done so much for Canadian art, will not let this opportunity pass unnoticed. Certainly it will know how to acknowledge and honour its great artists.”

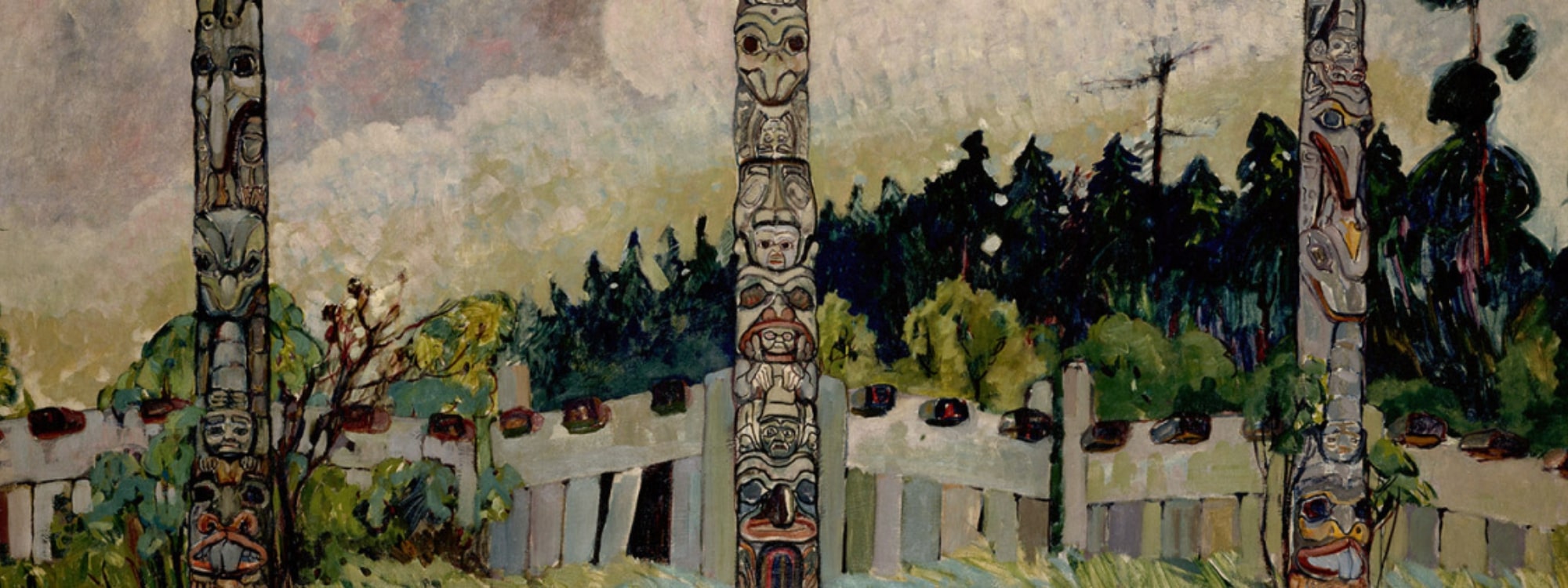

Whether the credit must go to Woo and her tough constitution or not, the address was a great success. Both the Victoria daily papers gave it wide publicity in their issues of 4 March. The Daily Colonist said in part: “An eloquent plea for a more tolerant and sympathetic view of modern art was made by Miss Emily Carr, a Victoria artist, who is at the same time one of Canada’s recognized leading exponents of the new movement, in the course of an address which she gave yesterday afternoon before an audience which filled the Crystal Garden concert hall to its utmost capacity. In her exhibition of fifty or more canvases depicting West Coast Indian totems and village scenes, Miss Carr had an even more powerful argument than she advanced in her searchingly clever, humorous and analytical talk, although the latter helped many to examine the pictures with a fresh understanding and appreciation. The tremendous interest which the subject has for Victorians was amply demonstrated in the unusually big attendance, which constitutes something in the nature of a record in the club annals. And the eagerness of many nonmembers to see the pictures has resulted in arrangements being made by the Crystal Garden management to continue the exhibition today and tomorrow from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily.”

These comments were paralleled by the Victoria Daily Times. After a quite lengthy quotation from the address, the Times reporter went on to say: “The foregoing summarizes the earnest plea made by Miss Emily Carr, noted Victoria artist, before the Women’s Canadian Club yesterday afternoon for a greater spirit of tolerance and understanding towards the modern artist who, striving to portray not merely the photographic delineations of Canada’s beauty, but the very spirit and soul of its majestic appeal, deserts the traditional school of art for that of the impressionist.

“Miss Carr’s plea was made the more forceful by the exhibition of her pictures, held in the Crystal Garden gallery, in conjunction with the address. Two distinct phases in the development of her art were apparent in the collection, the first, while virile and powerful in design, tending more to the ‘photographic’ interpretation of scenes at the Indian villages on the west coast and in other parts of the Province, while her later work showed a groping after and a conception of the spirit underlying the primitive art of the Indians, as expressed in her amazing studies of totem poles. The pictures will remain on view to the public at the Crystal Garden gallery today and tomorrow from 10 until 5 o’clock.”

The address is typical of Emily Carr. It is forthright, challenging, down-to-earth, witty. It reflects the philosophy of her whole life as a painter, a philosophy which was centred around an insistence on complete integrity, independence, and honesty, a philosophy which she adhered to, lived and worked within throughout her whole career. She believed firmly that the artist must speak clearly to people, must speak in terms of actual experience but must address particularly the spirit and the soul. She was always, and increasingly in her middle and later years, opposed to photographic realism in painting. She felt that there was a much higher role for the true artist and of this he must be aware, and this role he must play.

There is a most interesting brief passage in one of Emily’s “Journals” where she put the whole thing very clearly: “Be careful that you do not write or paint anything that is not your own, that you don’t know in your own soul. You will have to experiment and try things out for yourself and you will not be sure of what you are doing. That’s all right, you are feeling your way into the thing. But don’t take what someone else has made sure of and pretend it’s you yourself that have made sure of it, till it’s yours absolutely by conviction. It’s stealing to take it and hypocrisy and you’ll fall in a hole. . . . If you’re going to lick the icing off somebody else’s cake you won’t be nourished and it won’t do you any good—or you might find the cake had carraway seeds and you hate them. But if you make your own cake and know the recipe and stir the thing with your own hands it’s your own cake. You can ice it or not as you like. Such lots of folks are licking the icing off the other fellow’s cake!”

The address which is now published for the first time and the notices in the contemporary press of Victoria are interesting and significant. They show a degree of public interest in Emily Carr’s work as a painter which has perhaps not always been realized as existing at so early a date as 1930. True, she had had her exhibition in Ottawa some four years earlier. She had contributed single canvases to exhibitions in Eastern Canada, in Vancouver, in the United States, and even in Europe, but the Victoria exhibition of her paintings together with the opportunity given her to speak of her work is a very important point in the history of public reaction to her painting. Unfortunately, the interest indicated in the newspapers was not sustained and Miss Carr had a long period of struggle and only semi-recognition ahead of her. Indeed, final recognition did not come until her books began to be published by the Oxford University Press—the first of them, Klee Wyck, in 1941. This volume and others that followed attracted a new kind of attention from a new group of people to the work of this extraordinary woman.

I am very grateful to be associated with the Oxford University Press in the publication of this unusual address in this tenth anniversary year of Emily Carr’s death.

IRA DILWORTH

Vancouver, British Columbia (1955)

Fresh Seeing by Emily Carr

I hate like poison to talk. Artists talk in paint—words do not come easily. But I have put my hate in my pocket because I know many of you cordially detest “Modern Art.” There are some kinds that need detesting, done for the sake of being bizarre, outrageous, shocking, and making ashamed. This kind we need not discuss but will busy ourselves with what is more correctly termed “Creative Art.” I am not going to tell you about the ’ists and ’isms and their leaders, and when they lived and when they died. You can get that out of books. They all probably contributed something to the movement, even the wild ones. The art world was fed up, saturated, with lifeless stodge—something had to happen. And it did.

I want to tell you some of the things that I puzzled about when I first saw it and wondered what it was all about. It stirred me all up, yet I couldn’t leave it alone. I wanted to know why. When I went to Paris in 1911 I was lucky enough to have an introduction to a very modern artist. Immediately I entered his studio I was interested. Later I took lessons from him. Yet, strange to say, it was his wife, who was not an artist at all, that first gave me very many of the vital little sidelights on modern art. She really loved and appreciated it, not for her husband’s sake (they scrapped), but for its own sake. She evidently admired his work more than she admired him. He was a fine teacher and his work was interesting and compelling, but his wife read and thought and watched, and she had the knack of saying things.

To return to the term “Creative Art.” This is the definition a child once gave it: “I think and then I draw a line round my think.” Children grasp these things more quickly than we do. They are more creative than grown-ups. It has not been knocked out of them. When a child draws he does so because he wants to express something. If he draws a house he never fails to make the smoke pour out of the chimney. That moves, it is alive. He feels it. The child’s mind goes all round his idea. He may show both sides of his house at once. He feels the house as a whole, why shouldn’t he show it? By and by he goes to school and they train all the feeling out of him. He is told to draw only what he sees, he is turned into a little camera, to be a mechanical thing, to forget that he had feelings or that he has anything to express; he only knows that he is to copy what is before him. The art part of him dies.

The world is moving swiftly and the tempo of life has changed. What was new a few years back is now old. There have been terrific expansions in the direction of light and movement; within the last few years these have altered everything. Painting has felt the influence. Isn’t it reasonable to expect that art would have to keep pace with the rest? The romantic little stories and the mawkish little songs don’t satisfy us any longer. Why should the empty little pictures? The academic painting of the mid-nineteenth century in England had entirely lost touch with art in running after sentiment.

When Paul Cézanne, the great Frenchman who did so much to show the world that there was something so much bigger and better for art, came, he was hooted at, called crazy, ridiculed! Now we realize what he and the men who followed him did to open the way, to change our vision. Cézanne’s real business was not to make pictures, but to create forms that would express the emotions that he felt for what he had learnt to see. He lost interest in his work as soon as he had made it express as much as he had grasped.

Lawren Harris says: “The immediate results of ‘Creative Art’ are irritating and foreign.” One thing is certain—it is vital and alive. The most conservative artists, although they may rant and rail, are consciously or unconsciously pepping up their work. They know that if they do not, it is going to look like “last year’s hat” when it goes into the exhibitions. They are using more design, fresher colour, and the very fervour with which they denounce Modern Art shows how it stirs them up. So also with the onlooker. It may stir and irritate him, but isn’t it more entertaining and stimulating even to feel something unpleasant than to feel nothing at all—just a void? There is such a lot of drab stodginess in the world that it’s delicious to get a thrill out of something.

Willinski says: “A high proportion of the naturalistic painting of the world was done in the nineteenth century, due partly to the fact that the invention of the camera greatly enhanced this technique.” Certain of the camera’s limitations are now universally admitted.

The camera cannot comment.

The camera cannot select.

The camera cannot feel, it is purely mechanical.

By the aid of our own reinforcement we can perceive roughly what we desire to perceive and ignore, as far as is physically possible, what we do not desire to perceive. No work of real value is produced by an artist unless his hand obeys his mind. The camera has no mind.

We may copy something as faithfully as the camera, but unless we bring to our picture something additional—something creative—something of ourselves—our picture does not live. It is but a poor copy of unfelt nature. We look at it and straightway we forget it because we have brought nothing to it. We have had no new experience.

Creative Art is “fresh seeing.” Why, there is all the difference between copying and creating that there is between walking down a hard straight cement pavement and walking down a winding grassy lane with flowers peeping everywhere and the excitement of never knowing what is just round the next bend!

Great art of all ages remains stable because the feelings it awakens are independent of time and space. The Old Masters did the very things that the serious moderns of today are struggling for, namely, trying to grasp the spirit of the thing itself rather than its surface appearance; the reality, the “I Am” of the thing, the thing that means “you,” whether you are in your Sunday best or your workday worst; or the bulk, weight, and impenetrability of the mountain, no matter if its sides are bare or covered with pine; the bigger actuality of the thing, the part that is the same no matter what the conditions of light or seasons are upon it—the form, force, and volume of the thing, not the surface impression. It is hard to get at this.

You must dig way down into your subject, and into yourself. And in your struggle to accomplish it, the usual aspect of the thing may have to be cast aside. This leads to distortion, which is often confused with caricature, but which is really the emotional struggle of the artist to express intensely what he feels. This very exaggeration or distortion raises the thing out of the ordinary seeing into a more spiritual sphere, the spirit dominating over the subject matter. From distortion we take another step on to abstraction where the forms of representation are forgotten and created forms expressing emotions in space rather than objects take their place; where form is so simplified and abstracted that the material side, or objects, are forgotten—only the spiritual remains.

This use of distortion accounts for the living qualities in many of the Old Masters—the dear, queer old saints with hands and faces and bodies all distorted, but with their spirits shining through with such a feeling of intense beauty. It was not that these men could not draw. Do you think that their things would have lived all through the centuries if there was nothing more to them than bad drawing? It was the striving for the spiritual above the material. Had they made the bodies ordinary the eye would have been satisfied with the material side. It would have looked no further and would have soon tired. But, being raised up above the material, the spiritual has endured and will for all ages. The early Christian artists, seeking to perceive an aspect of man suitable for a divine image, thought away the flesh and distorted the human body to make it as uncorporeal as possible.

As the ear can be trained by listening to good music, so the eye can be trained by seeing good pictures.

People complain that modern art is ugly. That depends on what they are looking for and what their standard of beauty is. In descriptive or romantic art they are looking for a story or a memory that is brought back to them. It is not the beauty of the picture in itself that they observe. What they want is the re-living of some scene or the re-visiting of some place—a memory.

The beauty concealed in modern art consists more in the building up of a structural, unified, beautiful whole—an enveloped idea—a spiritual unity—a forgetting of the individual objects in the building up of the whole.

By the right disposition of lines and spaces the eye may be led hither and thither through the picture, so that our eyes and our consciousness rest comfortably within it and are satisfied. Also, by the use of the third dimension, that is, by retrogression and projection, or, to be plainer, by the going back and the coming forward in the picture—by the creation of volume—we do not remain on the flat surface having only height and breadth but are enabled to move backward and forward within the picture. Then we begin to feel space. We begin to feel that our objects are set in space, that they are surrounded by air.

We may see before us a dense forest, but we feel the breathing space among the trees. We know that, dense as they may appear, there is air among them, that they can move a little and breathe. It is not like a brick wall, dead, with no space for light and air between the bricks. It is full of moving light playing over the different planes of the interlocked branches. There are great sweeping directions of line. Its feelings, its colour, its depth, its smell, its sounds and silences are bound together into one great thing and its unfathomable centre is its soul. That is what we are trying to get at, to express; that is the thing that matters, the very essence of it.

There are different kinds of vision. The three most common are practical, curious, and imaginative. Because these are habitual in daily life we have become accustomed to use them when looking at pictures, and all three of them cause their owner to be interested in practical matters, in the data which the picture records, in matters of skill, in storytelling, etc. If anyone using only these three types of vision looks at a picture in which the trees have, let us say, been made universal instead of particular (that is to say, in which they have had all their pictorial, meaningless branches and wiggles omitted and the essential shape then changed to meet the needs of design), he is more or less incensed. His practical vision at once asks: What are they? When told they are trees, he is angry and says: “They don’t look like it.” The fact that the artist has aimed at another goal than that of copying is beyond his comprehension. It doesn’t exist for a person using only these three types of vision.

The attainment of further adventure in seeing pictures depends on what is called pure vision. This is the vision that sees objects as ends in themselves, disconnecting them from all practical and human associations. In that direction only lie the new horizons which have been revealed for us by the modern movement. All forms in nature can be reduced to primary geometric solids—that is, a mountain may be represented by a cone or pyramid, a tree-top as a cube or sphere, the trunk as a cylinder. So to reduce such objects for purposes of pictorial design simplifies the problem to its lowest possible terms. When a picture is looked at, the relation of its forms and spaces should be felt emotionally rather than thought about intellectually. Today we have almost lost the ability to respond to pictures emotionally—that is, with aesthetic emotion. Modern art endeavours to bring this ability to consciousness again.

The question of things not looking what they are is often a stumbling block to the observer who would like to understand modern art. There may be a bigger thing that the artist is striving for in his picture than the faithful portraying of some particular trees or other objects. It may be some great emotion that he feels sweeping through the landscape. We will say there is a high mountain of overpowering strength in his picture that seems to dominate everything, to make the rest cower and shrink. Possibly that is the thing he focuses his attention on, the thing he is trying to express. He sacrifices everything to that emotion, changing his forms, selecting, omitting, bending every other thing to meet that one desire. Everything in his picture must help to envelop and unify his idea.

It would, I feel, be impossible to speak on Canada and creative art without mentioning the Group of Seven and the splendid work they have done and are doing for art in Canada.

Some of you will have read the Canadian Art Movement by F. B. Housser. It is in our Public Library, which, by the way, has some very helpful art books. The Yearbook of Canadian Art[B] by Bertram Brooker and Modern French Painters by Jan Gordon—these books and others are a great help to those isolated as we are from the big art centres of the world. The Provincial Library, also, has some fine books on art and doubtless the librarians, if they find sufficient interest is taken in this subject, will add more.

The Group of Seven consists of a small group of men, some with academical training, some without; most of them are Canadian by birth, all are Canadians in the best sense of the word. They were mostly busy men with livings to make, but they loved art and in their holidays they went up to the country above Lake Superior to paint and were enthralled by it, put their best into it and took the best out of it. I will quote what one of their members, Lawren Harris, says of their evolution: “The source of our art is not in the achievements of other artists in other lands, although it has learned a great deal from these.

Our art is founded on a long and growing love and understanding of the North, in an ever clearer experience of oneness with the informing spirit of the whole land and a strange brooding sense of Mother Nature fostering a new race and a new age. So the Canadian artist in Ontario was drawn North and there at first devoted himself to Nature’s outward aspect, until a thorough acquaintance with her forms, growth and idiosyncracies and the almost endless diversity of individual presences in lakes, rivers, valleys and forests, led him to feel the spirit that informs all these.

Thus, living in and wandering over the North and at first more or less copying a great variety of motives, he inevitably developed a sense of design, selection, rhythm and relation to individual conformity to her aspect, moods and spirit. Then followed a period of decorative treatment of her great wealth and design and colour patterns, conveying the moods of seasons, weather and places. Then followed an intensification of mood, that simplified form into deeper meaning and was more vigorously selected and sought to have no element in the work that did not contribute to a unified, intense expression. The next step was the utilization of the elements of the North in depth, in three dimensions, giving a fuller meaning, a more real sense of the presence of the informing spirit.”

These men are a group that Canadians may well be proud of. They have opened up wonderful fields for art in Canada, burst themselves free, blazed the trail, stood the abuse and lived up to their convictions. At Wembley in 1924 their work was recognized by critics familiar with the best modern work of Europe. Later they exhibited by invitation in Paris as well as all the big centres in the United States. One of the splendid things about them is their willingness to help those who are struggling to see things in a broader way.

What about our side of Canada—the Great West, standing before us big and strong and beautiful? What art do we want for her art? Ancient or modern? She’s young but she’s very big. If we dressed her in the art dresses of the older countries she would burst them. So we will have to make her a dress of her own. Not that the art of the Old World is not great and glorious and beautiful, but what they have to express over there is not the same as we have to express over here. It is different. The spirit is different.

Everyone knows that the moment we go from the Old Country to the New, or from the New to the Old, we feel the difference at once. European painters have sought to express Europe. Canadian painters must strive to express Canada. Misty landscapes and gentle cows do not express Western Canada, even the cows know that. I said to a farmer in Scotland once: “That fence wouldn’t keep out a Canadian cow.”

“You are right,” he replied, “it would not. Your cows are accustomed to fighting their way through the bush. When they are shipped here, it takes twice as many men and twice as high a fence to make them stay put.” So, if the country produces different cow-spirit, isn’t it reasonable that it should produce different artist-spirit? Her great forests, wide spaces, and mighty mountains and the great feel of it all should produce courageous artists, seeing and feeling things in a fresh, creative way. “Modern” we may call it, but remember, all modern art is not jazz. Canada wants something strong, big, dignified, and spiritual that shall make her artists better for doing it and her people better for seeing it.

And we artists need the people at our back, not to throw cold water over us or to starve us with their cold, clammy silence, but to give us their sympathy and support. I do not mean money support. I mean moral support; whether the artists are doing it in the old way or in the new way, it does not matter, so long as it is in the big way with the feel and spirit of Canada behind it.

People need not like creative art. It is not a sin if they don’t, but they lose an awful lot of joy out of life by not trying to understand it. It opens up a new world for those who seek to understand it. Lots of artists sort of hanker for the adventure of it but are afraid of the public. They couldn’t stand up against the sometimes just and sometimes unjust ridicule of the people or the press. They squeeze and little themselves, hoping to please or sell. I tell you it is better to be a street-sweeper or a char or a boarding-house keeper than to lower your standard. These may spoil your temper, but they need not dwarf your soul.

Some say the West is unpaintable and our forests monotonous. Oh, just let them open their eyes and look! It isn’t pretty. It’s only just magnificent, tremendous. The oldest art of our West, the art of the Indians, is in spirit very modern, full of liveness and vitality. They went for and got so many of the very things that we modern artists are striving for today. One frequently hears the Indians’ carvings and designs called grotesque and hideous. That depends on the vision of the onlooker.

The Indian used distortion or exaggeration to gain his ends. All nature to him seethed with the supernatural. Everything, even the commonest inanimate objects—mats, dishes, etcetera—possessed a spirit. The foundation that the Indian built his art upon was his Totem. He did not worship it, but he did reverence it tremendously. Most of the totems were animal representations, thus animal life played a great part in the life of the Indian and his art.

They endowed their totem with magic powers. In the totem image the aspect or part of the animal that was to work magic was distorted by exaggeration. It was made as the totem-maker saw it—only more so. The Indians were supposed to partake of the nature of their totems. That is to say, eagles were supposed to be daring and fierce, ravens cunning and tricky, wolves sly and fierce. The beaver is expressed by his huge front teeth, his hands usually clasping a stick and his cross-hatched tail tucked up in front of him. These are his most particular and characteristic emblems. They represent him as a brave, splendid creature, an ancestor to be proud of.

There is all the difference in the world between their beaver and the insignificant little animal that we take for our national emblem. We belittle him, only give him his surface representation. The Indian goes deeper. He expresses the thing that is the beaver, glorifying him, showing his brave little self that can saw down trees and build his house, energetic, courageous. They show the part of him that would still be beaver even if he were skinned. Here is a striking instance of the difference between Representative and Modern Art.

In the next room you will see two different types of pictures. Some will like one kind, some the other, and some neither. The subjects are much the same, but the viewpoint is different. In the older canvases things are carefully and honestly correct as to data. The late Dr. Newcombe, our best authority on West Coast material, agreed to that. The others are the newer school. Here I wanted something more—something deeper—not so concerned with what they looked like as what they felt like, and here I really was sweeping away the unnecessary and adding something more, something bigger.

It is not my own pictures I am pleading for. They are before you to like or to dislike as you please. That is immaterial. For the joy of the artist is in the creating, the making of his picture. When he has gone as far as he understands, pushed it to the limits of his knowledge and experience, then for him that picture is a thing of the past, over and done with. It then passes on to the onlooker to get out of it what there is for him in it, for what appeals to him, what speaks to him; but the struggles, hopes, desires of the artist are all centred on his next problem: how to make his next picture a little better, profiting by his failures and experiences in the last, determined to carry the next one a little further along, to look higher and to search deeper, to try to get a little nearer to the reality of the thing.

The plea that I make to you is for a more tolerant attitude toward the bigger vision of Creative Art—a quiet searching on your part to see if there is sincerity before you condemn.

The National Gallery of Ottawa is trying to help the whole of Canada to a better appreciation of art by sending loan collections of both conservative and modern pictures over the country. In the West, modern work was rejected. They were asked not to send any more. How can we grow if we are not permitted to see the progressive work? When other parts of Canada are growing and want to grow, why must we stand still?

When I was young I had a great fear and dislike of monkeys. By and by I came to see this was foolish and I decided to get over it. So I went at every opportunity I got to the London Zoo and I looked the monkeys fairly and squarely in the face. Then I got interested, then fascinated. Now I own one and she has brought all kinds of fun into my life. If Ottawa should send out modern work for us to see, do think of my monkey and remember that tastes can be acquired.

0 comments