Introduction

The entry following one dated October 19, 1935 in Emily Carr’s journal reads: For the last week I have been struggling to construct a speech. Today I delivered it to the Normal School students and staff. It was on “The Something Plus in a Work of Art.” I don’t think I was nervous; they gave me a very hearty response of appreciation, all the young things. (It hit them harder than the three professors, all rather set stiffs.) “Something quite different from what we usually get,” they said.

The most pompous person said after a gasp of thanks—“I myself have seen that same yellow that you get in that sketch, green that looked yellow. Yes, what you said about the inside of the woods was true, quite true—I’ve seen it myself.” Pomposity No. 2, very tidy and rather fat, introduced himself with a bloated complacency, “I am so and so”—a long pause while he regarded me from his full manly height. “I have seen your work before but never met you.” After this extremely appreciative remark, he added, “Most interesting.” Whether he meant the fact we had not met before or my talk was left up in the air.

The third Educational Manageress was female. She said, “Thank you. It was something quite different from the talks we usually get. I am sure I do not need to tell you how they enjoyed it—you could see that for yourself by their enthusiastic, warm reception.” They did respond very heartily. One boy and one girl rose and said something which sounded genuine, though it could not penetrate my deaf ear. I could only grin in acknowledgement and hope it was not something I ought to have looked solemn or ashamed over.

I was interested in my subject and not scared, only intent on getting my voice clearly to the back of the room and putting my point over. Afterwards I wished I had faced those young things more steadfastly. I wished I had looked at them more and tried to understand them better. If ever I speak again I’m going to try and face up to my audience squarer, to take courage to let my eyes go right over them to the very corners of the room, and feel the space my voice has to fill and then to meet all those bright young eyes. There they are, two to each, some boring through you—waiting. Of course I had to read my talk and that makes all the fuss of spectacles on for that and off for seeing the audience.

It must be very wonderful to be a real speaker and to feel one’s audience as a unit, to feel them sitting there, to feel them responding, at first quizzically then interested, finally opening up, giving whole attention to what you yourself have dug up, what you have riddled out of nature and what nature has riddled into you. Suppose you got up with a mouthful of shams to give them and you met all those eyes. How you would wither up in shame! What a sneak and an imposter if you did not believe sincerely in what you were saying and were not trying yourself to live up to that standard!

The text of the speech itself (dated October 22, 1935) was among Miss Carr’s papers.

Something Plus in a Work of Art

Real Art is real Art. There is no ancient and modern. The difference between the two is not in art itself, but lies in environment, in our point of view, and in the angle from which we see life.

The greatness of an artist’s work is measured by the depth and intensity of his feelings and emotions towards it, and towards life, and how much of these he has been able to implant and express in that work.

Perhaps one reason for the great and lasting power of the work of the old masters may have been partly their mode of living. In those days a man did not fritter away so much of his time and strength in running to and fro. His attention too was not rushed from one interest and excitement to another as it is in these days. His life was governed by a few strong simple motives. When he attacked anything like art he did so from the depths of his being, from vast reservoirs of stored vitality and ideas based on fundamentals so deeply rooted that they grow and blossom in those canvases still in spite of the time that has passed since their making.

Much of what we call “Modern Art” is, even yet, more “experiment” than “experience.” Between the old idea of painting and the new idea of painting, there came a blank stretch, during which much of the meaning and desire for deep earnest expression lay dormant. Something crept in that had not been in the old art. Something which did not touch the roots of art, but floated on the surface with a skin-deep sentimental mawkishness. There were still grand and earnest workers scattered among the artists, but into the real idea of art crept the idea of money rather than the idea of expressing. Gradually the standard of pictures was lowered. Men painted from a different motive, to get money, to please patrons rather than to express their art. They told stories in paint. They preached sermons in paint. They flattered people in paint. They reminded them by their pictures of places and things that they had once seen, and people went delightedly tripping back through their memories, not in the least stirred by the art in the pictures, but pleased with their recollections of what they had seen with their own eyes.

This was all very well for those that it satisfied, but it was not art, and there were others who craved the real thing, who wanted to go deeper, whose souls revolted within them at the sham, and wanted something inspiring to push forward into. They wanted the power behind the thing—the weight of the mountain, not the pile of dirt with grass spiking the top.

There was a revolt against all this meaningless softness and emptiness of expression, this superficial representation, and the consequence was the “Modern Movement” in art, which was a brave fierce rebellion. It was experimentation—a burning of bridges by these brave ones—a going back to the beginning, with the belief that the fundamentals which the ancients had used were still available to art, if they rooted up all the clogging sentimentality, and dug right down to the base of things, as the simple, earnest workers had done years before.

It was necessary for these pioneers of the Modern Movement to try all kinds of ways and means to get what they were after. They worked with one eye turned way back towards the simplicity and intensity of the primitives, and the other rolled forward towards the expressing of the tumult and stress of modern life. People laughed at them, called them crazy, and refused to acknowledge the sincerity of them or their work. But they stuck, intent on putting the something back into art that had been lost. So they experimented, tried this means and that, gradually weeding out what did not count, and building onto what did. Even the things that were discarded made their contribution. When they were abandoned it was to give place to something better, but the fact of their being abandoned showed growth, healthy growth that is still going on. You have only to go into a room full of pictures painted in the last fifty years by people who have not as yet come under the influence of “Modern Art” to realize what that growth has been.

Of course the movement has its empty shouters, the usual rag, tag and bobtail who follow every demonstration because of the noise and excitement, picking up minor and unnecessary details and passing over the essentials, shouting “Modern Art” meaninglessly, and trying to get, without working and wrestling for it, what the man who has thought long and toiled earnestly has got. But the best of the Modern Movement goes serenely on collecting a very mighty following—it continues to come slowly and surely into its own.

Now there are as many ways of seeing things as there are pairs of eyes in the world, and it is a mistake to expect all people to see all things in the same way. Also it is a mistake for anyone to try to copy another’s mode of seeing, instead of using his own eyes and finding his own way of looking at things. The more you look, the more is unfolded for your seeing, till bye and bye the fussy little unimportant things disappear, and the bigger meanings like power, weight, movement, etcetera will make themselves felt. To express these, it is necessary, as it is in everything else, that the artist should have some knowledge of the mechanics of painting, know how he can produce what he wishes to express. He must know what to look for. He must know what constitutes a picture. Also he must realize what there is in any special subject to produce in him the desire to express it.

A picture is the presentation of a thought that has come to us, either from something we have seen or something that we have imagined. We want to convey the meaning of what has passed through our mind as a result of coming in contact with that special subject. Our first objective must be, however, to pull it forth into visibility, so that we can see with our own eyes what our minds have grasped. If our minds have not recorded anything definite, we have nothing to give.

If we study our subject carefully, we will discover that there was some particular reason why we selected that subject; we either saw or felt something that appealed to us, that spoke more definitely to us than the rest of our surroundings did. It may have been colour, or line, or movement, or light, or texture. It may have been the combination of all these things. At any rate, all these elements must take their places in our composition, though none of them will be our subject. That will be both hidden in, and disclosed by, these elements. Everything should contribute definitely to it but nothing should overshadow it. The ideal that our picture is built to should transcend all the rest.

Before starting your picture, you first must have a desire, and you must have material; but above all these things, you must form your ideal and build it up. Sometimes the ideal forms itself complete, in a flash, but sometimes you must hunt and hunt, as it were, for a loose end to begin at, then follow it through all its snarls and windings till it comes out the other end of your picture, binding ideas together as it proceeds, until your ideal stands complete before you. The biggest and perhaps the hardest thing in painting is to be true to your ideals.

Suppose six different artists sat before the same subject. Provided they wore blinkers, or did not peep at each other’s canvases, but built each according to his own ideal of the subject, carrying it to its fulfillment, it is safe to say that no two of the pictures would be alike—providing, that is, that each had been honest with himself and his ideal.

Undoubtedly it is very helpful to see the work of others, to note what mechanics they have used, what their approach has been, how they expressed themselves, but the real worker must not be too biased by what another artist does. He must strike out and speak for himself, if his work is to be of any real value to himself or to others.

There are artists who force some strangeness that they do not feel into their work, to make it startling and original, violently different from that of others, but this work is not lasting, because it has no foundation in anything true, and its motive is not sincere.

The painter passes through different stages in his work, where the separate elements in the making of a picture seem to him all-important. These elements troop before him, obtruding themselves and crying, “I am the all-important thing that goes to the making of your picture.” We get excited over each phase as it comes along. Form, colour, composition, balance, light and shade, rhythm and many more—these all are important, all have worth, but we must remember that they are only parts; not one of them is strong enough to carry the whole burden, to form the base whereon to build the ideal of our picture. All these things are superstructure; they must not overpower the main issue, but contribute to it.

One of the strongest characteristics of the Modern Movement is the use of design. It is so powerful an element we are almost tempted to think, “Ha! Now we have got to the root of the matter. This design will blend all our elements together. Design will make our picture complete, so that the eye can travel all around the canvas, be satisfied, and come to rest.” Very good, that is so, but is that all we want?

Are we content to rest in smug satisfaction? To please the eye alone? A thousand times No. We want exhilaration. We want incentive to push further on, we want to make thoughts and longings that will set us wondering, that will make us desirous to explore higher and deeper and wider, to see more, to understand more. Design we admit to be an extremely valuable asset to art, but we cannot stop there, stagnating with satisfied eyes; we must go on, because our souls cry out for more.

In preparing notes for this talk I discovered something that I was unaware of. I should not be giving the talk at all because I am only a worker, and workers should work and talkers should talk, and both had best stick to their own jobs and avoid getting mixed up. However, perhaps it is good for us to exchange sometimes, so that each may find the difficulties the other is up against. In this case, by making the effort, I discovered that material that was useable for a talk I gave some years ago was not useable for what I wanted to say today. The facts are the same, but I see them from a different angle. Things that seemed to me of vital importance then seem of secondary importance now. Nor can I find the things I want to say in the art books. They do not seem to be in them, but out in the woods and down deep in myself. Emerson says something to the effect: If I say a thing today, it is no reason that I will not say something different tomorrow. If we did not change we would not grow.

I did, however, come across a chapter in a little book called How to See Modern Pictures. The chapter was entitled “The Something Plus in a Work of Art,” and it seemed to coincide with what I was trying to get at. The author said something like this:

Having considered rather carefully that quality in pictures which is probably the most vital contribution of the Modern Movement in the world of art today—the quality of organization into design—we must now turn to the “something plus,” something beyond the literal content of the picture, something that distinguishes the great work of art.

How to See Modern Pictures by Ralph M. Pearson, 1925. Dial Press, New York.

Further on, he stated that this most elusive of all elements in a picture, this “something plus,” is born of the artist’s attempt to express the force underlying all things. It has to do with life itself: the push of the sap in the spring, heave of muscles, quality of love, quality of protection, and so on.

And again, quoting from another book, he said that one of the most important principles in the art of Japanese painting is called Sei Do. It means the transfusion into the work of the felt nature of the thing to be painted by the artist. Whatever the subject to be translated, whether river, mountain, bird, flower, fish or animal, the artist at the moment of painting it must feel its very nature which, by the magic of his art, he transfers into his work to remain forever, affecting all who see it with the same sensations he experienced when executing it. It is by expressing the felt nature of the thing, then, that the artist becomes the mouthpiece of the universe of which he is part and reveals it unto man through the “something plus” in the picture, the nature as well as the appearance of the life and forms about him.

The old masters of Europe, the Chinese and Japanese, the Greeks, the Byzantines, the Assyrians, the African negroes, the Indians of America, and many others through history, embodied this felt nature of the thing in their works of art, and it is when, as in these cases, this divine fire is tempered and controlled by design, that deathless work is born—work that takes its place as part of the universal language of man.

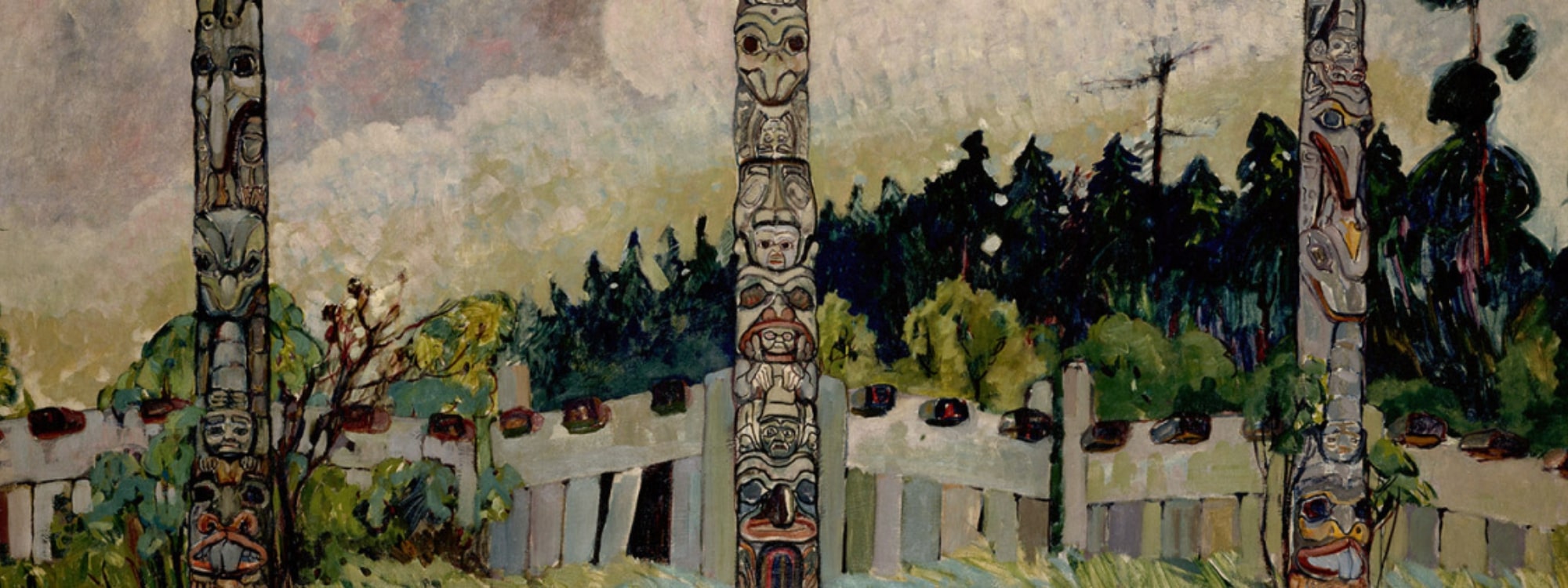

To bring this idea close to home, let us consider for a moment the grand early work of our West Coast British Columbia Indians. Their work has been acclaimed worthy to take its place among the outstanding art of the world. Their sensitiveness to design was magnificent; the originality and power of their art forceful, grand, and built on a solid foundation, being taken from the very core of life itself.

These Indians were a people with an unwritten language. They could neither borrow nor lend ideas through written words. To find means to express, they were obliged to rely on their own five senses, and with these, to draw from nature direct. They saw, heard, smelled, felt, tasted her. Their knowledge of her was by direct contact, not from theory. Their art sprang straight from these sources, first hand. They looked upon animals (through which they mostly expressed their art) as their own kindred.

Certain of the animals were more than that: they were their totems and were regarded by them with superstitious reverence and awe. Not being able to write their names, they represented themselves by picturing the particular animal which they claimed for a crest. Every time he pictured this crest the Indian identified himself closer with the creature. To many of the animals they attributed supernatural powers. People who were of the same crest or totem were bound to each other by closer ties than blood, and did not intermarry. A man did not kill or eat the animal of his totem, but did all he could to propitiate it.

He also believed himself possessed of the special attribute of his totem. If he were an eagle he boasted of strength and fierceness. Ravens were wily, wolves cunning, and so forth. The Indians carved their totems on great cedar poles and stood them in front of their dwelling houses; they painted them on the house fronts and on their canoes. In travelling from one village to another, people were assured of a welcome from those of their own totem. Thus the Indian identified himself so completely with his totem that, when he came to picture it, his felt knowledge of it was complete, and burst from him with intense vigour. He represented what it was in itself and what it stood for to him. He knew its characteristics, its powers and its habits, its bones and structure.

Added to this stored-up knowledge waiting to be expressed was the Indian’s love of boasting. Each Chief who raised a pole thrilled with pride, and wanted to prove that he was the greatest chief of his tribe. The actual carver might be a very humble man, but as soon as he tackled the job he was humble no longer. He was not working for personal glory, for money, or for recognition, he was working for the honour and glory of his tribe and for the aggrandizement of his Chief. His heart and soul were in his work; he desired not only to uphold the greatness of his people but to propitiate the totem creature. The biggest things he was capable of feeling he brought to his work and the thing he created came to life—acquired the “something plus.”

Once I asked an Indian why the old people disliked so intensely being sketched or photographed, and he replied, “Our old people believe that the spirit of the person becomes enchained in the picture. When they died it would still be held there and could not go free.” Perhaps they too were striving to capture the spirit of the totem and hold it there and keep these supernatural beings within close call.

I think, therefore, that we can take it that the Indian’s art waxed great in the art of the world because it was produced with intensity. He believed in what he was expressing and he believed in himself. He did not make a surface representation. He did not feel it necessary to join its parts together in consecutive order. He took the liberty of fitting teeth, claws, fins, ribs, vertebra, into any corner of his design where they were needed to complete it. He cared nothing for proportion of parts, but he was most particular to give to every creature its own particular significance. The eyes he always exaggerated because the supernatural beings could see everywhere, and see more than we could. A beaver he showed with great front teeth, and cross-hatched tail. Each creature had its own particular things strongly brought out. The Indian’s art was full of meaning, his small sensitive hands handled his simple tools with a careful dexterity. He never hurried.

Why cannot the Indians of today create the art that their ancestors did? Some of them carve well, but the objective and the desire has gone out of their work. The “something plus” is there no longer. The younger generations do not believe in the power of the totem—when they carve, it is for money. The greatness of their art has died with their belief in these things. It was inevitable. Great art must have more than fine workmanship behind it.

It is unlikely that any one thing could ever again mean to these people what their art meant to their old, simple, early days. Reading, writing, civilization, modern ways, have broken the concentration on the one great thing that was dammed up inside them, ready at the smallest provocation to burst into expression through their glorious art.

0 comments