A new patient was put to bed, all his peculiarities noted, entered in the Doom Book. Had he one or two lungs? was he emaciated or naturally lean? cheerful dispositioned or grumpy? possessed of a poor appetite or just pernickety?

When this knowledge had been ascertained and recorded, Doctor McNair cast about for a couple of suitable visitors to cheer the newcomer. For me she selected Scrap.

Scrap opened my door inches—enough to squeeze her emaciated body through. It was that tiresome time after supper. You were too weary to do much and not yet ready for sleep. Scrap said,

“Doctor sent me. Do you mind?”

“I should say not! Won’t you sit down?”

My one chair was full of books. “I’ll sit up,” said Scrap, and scrambled to the top of the high gilt radiator which, except for that brief half-hour night and morning, never radiated. It did serve, however, as an exalted seat for a visitor. There was no danger of him sitting too hot either.

Scrap was dark, thin, hungry-eyed.

“My name is Mrs. Scrapton. Everyone calls me Scrap.”

“You don’t look like a Mrs.”

“I am though and have a baby six months old.” At mention of her baby the hunger in her eyes turned ravenous. “I have been here two months, two months without my baby!”

I asked, “Are you ever warm? ever comfortable? ever happy here?”

Scrap’s thin shoulders shrugged. “Not so bad once you get used to it, except—oh, I want my baby! Life here is like facing back, being a little girl again, told what to do, everything thought out for you, no responsibility, obey, drift, hope, that is all.”

She drew a bit of woolly baby knitting from the pocket of the great-coat she wore. Her cold little blue hands began to work. That was the beginning of a friendship that lasted as long as Scrap lasted.

My other visitor was Miss Angelina Judd. Angelina had sped swiftly from ‘Down’ to ‘Semi’, from ‘Semi’ to ‘Up’, yet still her case was not fully diagnosed. She had hay fever in a superlative degree. I had thought that her persistent sneeze was a young rooster crowing about the grounds. Down in the hollows, up on the hills, it came with mechanical precision. How that cockerel does wander! was my thought. Angelina combatted her complaint by valiantly ignoring it. She sneezed right on.

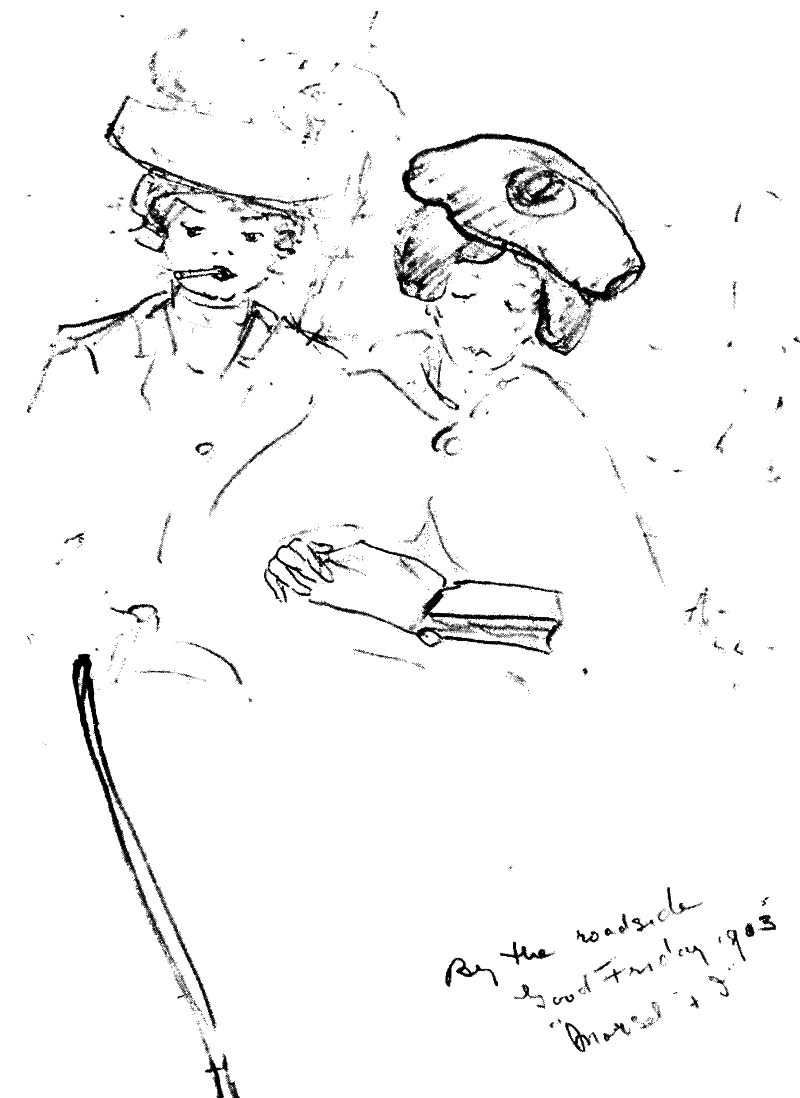

Emily and Scrap

By the roadside, Good Friday 1903

“Morsel and I”

Tap!—the opening of my door—a spasmodic bob. “A-choo! A-choo!” seven times repeated, then, “Doctor McNair sent me, and—” sneeze. “Do you like reading? What type? A-choo! A-choo!” She moved into the centre of the room. A question lurked in every sneeze, the violence of the spasm bumped her head on wall or furniture if she had not space.

Each week a great box of books came down from London addressed to Miss Angelina Judd. There was a book suitable for every patient; Angelina had previously probed every individual’s taste. If a patient were unequal to reading, Angelina read to him. The sense was all sneezed out but Angelina kept right on. She had a little mouth and small pointed teeth that gleamed as she read. Her nostrils were as black as coal buckets, burnt with nitrate of silver for her hay fever.

Like a striking clock, or a cow with a bell, Angelina by her sneeze kept us informed of her exact whereabouts.

When a box of new books came, she piled them up and up on her chest till the topmost was wedged under her chin, then she started on her rounds. “A-choo!” The first sneeze almost strangled her because of the library; of! flew the top book! That loosened the whole pile. “A-choo, bang! A-choo, bang!” all down the corridor. Angelina no sooner picked one up than she sneezed another off, but like the fine old battle-ship she was Angelina steamed straight ahead.

0 comments