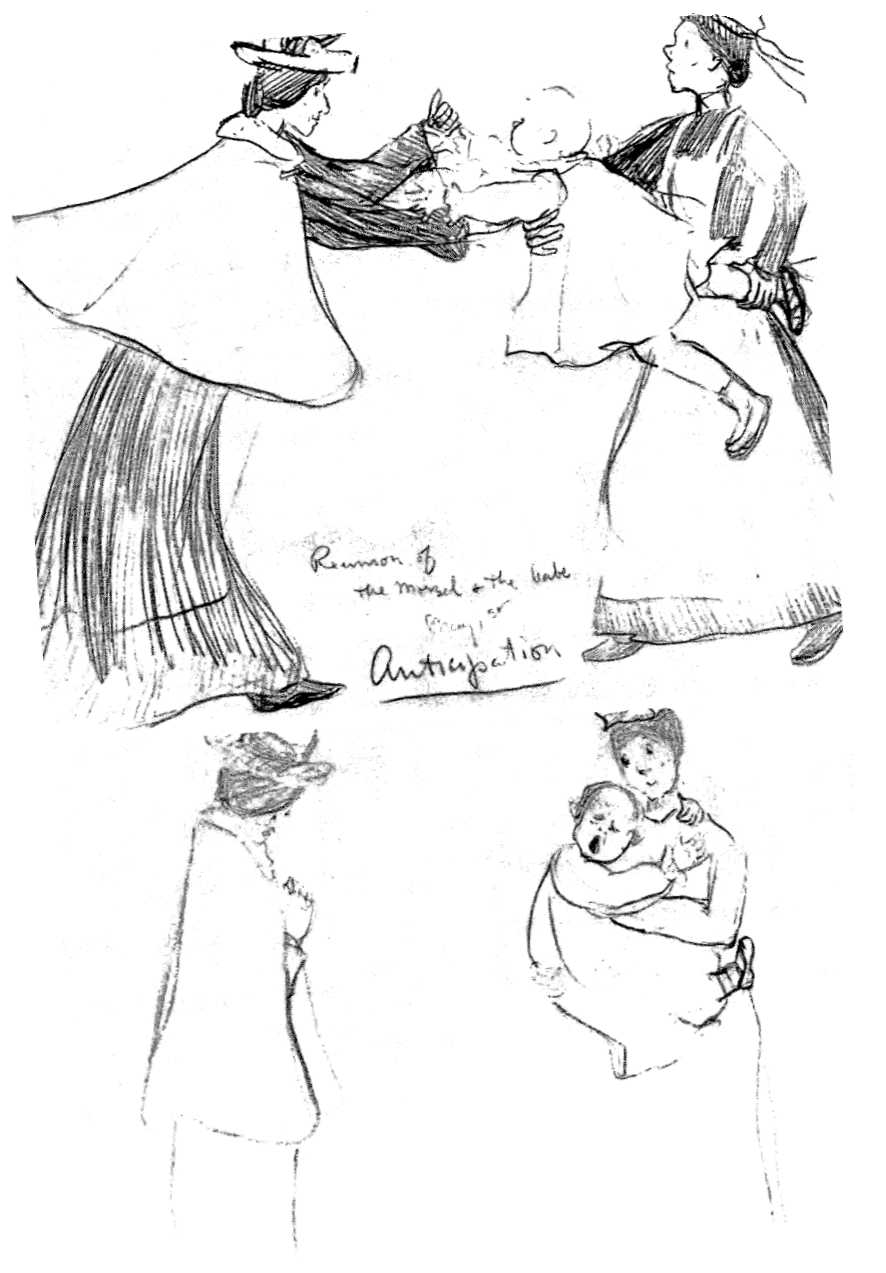

Scrap’s baby was nervy and fretful. She was brought occasionally to the San to visit her mother. Scrap had seen so little of her child, since the babe was old enough to take notice, that the child preferred her nurse. The woman spoiled her. Scrap groaned when the child turned away, but she dared not offend Nurse. The woman cared well for the infant.

Scrap and I had become very good friends. After supper in the evening my door would open—such a very little way, it seemed, when you remembered it was to admit an adult. I tossed a pillow up on to the top of the high gilt radiator that was always stone cold. Scrap climbed, took a bit of wool knitting from her great-coat pocket, told me the San news and little bits from her home letters. I read her pickings from my Canadian ones.

This night Scrap was full of one subject; she braced her toes against the edge of my bed and began excitedly, “What do you think?”

Scrap had been down-hearted lately. I was glad to see her animated.

“Has Doctor Sally given you permission to go home?”

“Almost as good! She is going to let me have baby here. Nurse will come too, of course, to look after baby. We will have the big room at the end of the west corridor. Baby in a cot close to my own bed. Just think! Aren’t you glad for me?”

I was silent. Scrap looked keenly into my face.

“You don’t think it good?”

“I do not, Scrap. I don’t care what two hundred and fifty Bottles say. Fretting lungs don’t heal. Lungs are all Doctor Bottle cares about. She is letting your baby take risks because she wants to add you to her list of cures.”

“I want my baby.”

“Several other mothers in the San doubtless want their babies too. They’ll enjoy having yours to dandle. How Dobbin will kiss her at every opportunity!”

Scrap winced! After a moment’s quiet she asked, “Shall I recite?”

“Please do.”

Her head was full of memorized odds and ends. We often wheedled half-hours by in this way; odd bits of poetry, little bits of prose drifted our thoughts away from San monotony. We were so surrounded by open air, it was easy to fly away on phrases, words that caught our fancy, travel through dark and space, leaving our bodies, our ailments and disappointments in the San. The bell for Turn-in rang. Scrap got down from the radiator.

Scrap’s Child

“Good-night. I am not bringing baby here.”

“Good-night, little Scrap.” She had thrown herself across my bed. For a moment things reversed; I, who was older than Scrap by several years, just then was her baby. Years did not count. Scrap needed something human to hug at that moment. Her husband was a cold man. He had never kissed Scrap nor allowed her to kiss him, since he learned she had T.B. He did not want her home, did not want every window in his house open to all the winds of heaven. I doubt if he would have allowed his child to go to the San. (Scrap had not told him yet of Doctor Bottle’s plan.) Scrap and I had a tiny cry, a big hug. She went to her room.

Life in the San did queer things to us. Was it our common troubles and discomforts? Or was it the open—birds, trees, space, sharing their world with us—that did it? I don’t know.

0 comments