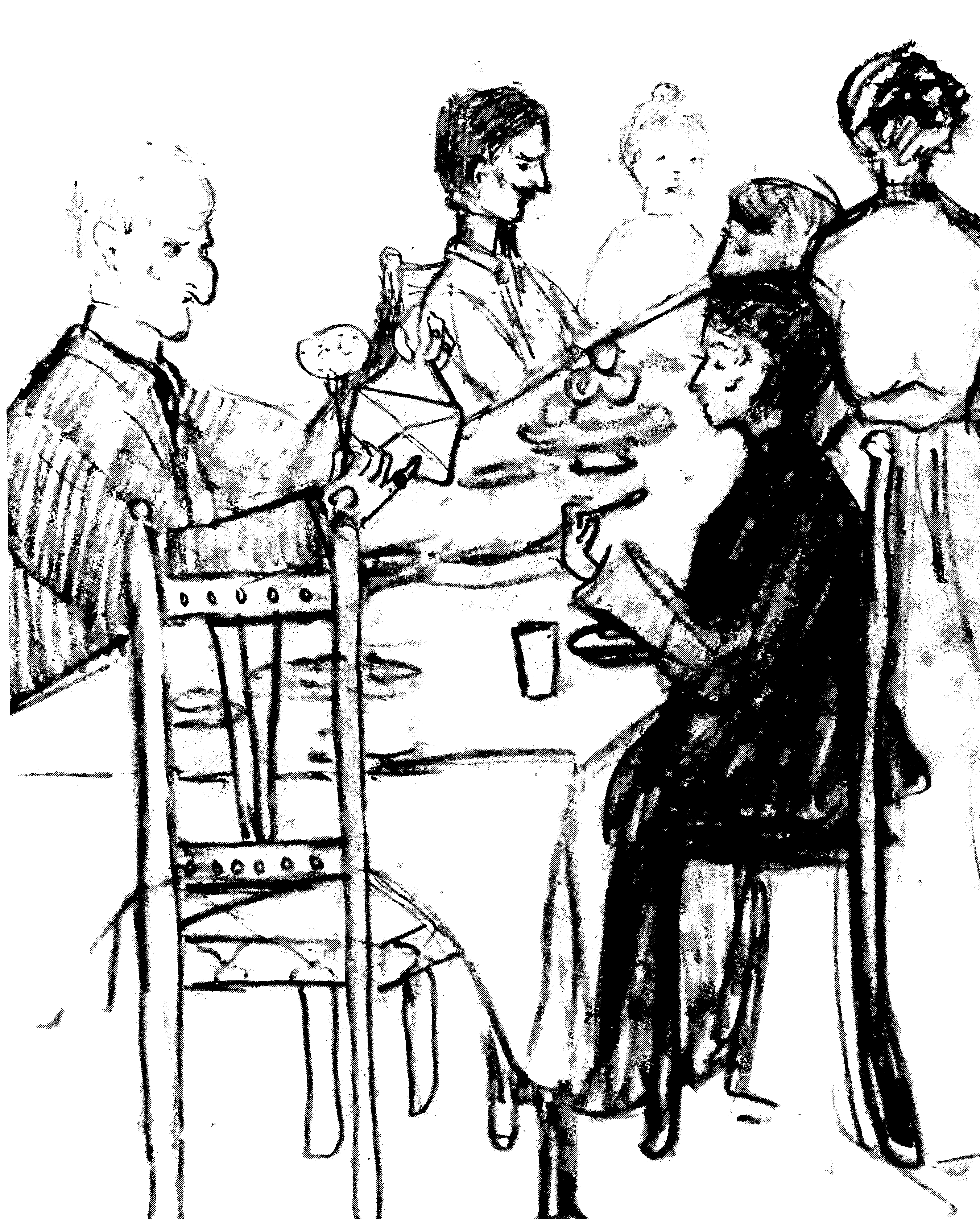

Forty and more fickle appetites strolled into the San dining-room, unenthusiastically took their places at table. A big part of the T.B. treatment was eating. Eating was compulsory. If patients refused to eat, the San refused to keep them as patients. Doctor McNair and Matron stood at a side-table and served. Were Doctor Bottle present, she dictated the helpings, cruel mountains of meat, vegetables and pudding helpings that would stagger the appetite of healthy men and women, and were positively loathsome to invalids.

The maids brought the hateful plates and slapped them down before each patient. You felt “pull-together” and “nausea” struggle in disgust and revolt as each patient surveyed her pile. When all were served Doctor and Matron took their places, one at either end of the long table, and started animated conversation. One by one the patients picked up their knives and forks and began to attack the food. It was bravely done.

There was an oldish school-master who had been attacked by T.B., a man accustomed to exact, not yield obedience. I saw this man scowl at his helping of spinach with a little boy’s fury; I saw little boy’s tears come into his eyes, tumble down his cheeks, hide their shame in his man’s beard. He beckoned a maid and whispered. In turn she whispered in the Doctor’s ear.

Clear and stern, Doctor McNair enunciated so that everyone could hear. “If Mr. Dane cannot eat spinach, substitute a double helping of carrot.” The oldish man smiled his thanks. “Sorry, Doctor, never could even as a boy.”

His neighbour, a florid woman nodded; “I entertain the same attitude towards carrots, Mr. Dane.”

Munch, munch, munch. Miss Dobbin, the woman opposite, chewed doggedly, determined to see the treatment through. She scorned the whimperings of the little neurotic on her left, the yawning envelope pinched between the knees of the hypocrite Marmaduke Jepson on her right. Between chews Miss Dobbin could not resist peeping to see if Marmaduke’s flip had landed true. His policy was to engage Doctor in an eye-to-eye conversation while he flipped. Great portions of his food flew into the waiting envelope; without so much as a glance his aim was accurate. Doctor was always holding Jepson up as an example to the rest, too, because of the speed with which he made clean his plate.

“Not that it has made much impression on your bones yet, Mr. Jepson. It will tho’. Patience, courage!”

Marmaduke

The beast depositing his food in an envelope as soon as Doctor’s back is turned prior to burying it.

“Thank you, Doctor, thank you, I try to be a credit to the San.”

“Credit! Ugh!” grunted Dobbin, as Jepson’s baked potato landed in the envelope.

Miss Bret laid down her knife and fork, closed her eyes; just for one second she must shut out the sight of food. She heard Doctor say:

“If this weather holds we shall have strawberries next week.” Food, food, always food!

A maid bent close, “Are you going to finish, Miss Bret?”

A silent head-shake. The maid removed the meat plate, substituted a generous cut of roly-poly pudding oozing jam. The struggle began all over again. Miss Bret knew that the plate of meat and vegetables would be taken straight to her room and must be eaten some time before supper. The jam roly-poly would join it there unless—. She severed six jammy little pieces, bolted them one after another like pills, controlling herself heroically against being sick.

“Suppose you can’t; suppose you won’t?” I once asked a patient.

“At bedtime it will be removed and a huge bowl of Benger’s gruel substituted for it.”

“Suppose you refuse that too?”

The patient rolled her eyes round in her head like an owl. “You couldn’t. Your people would be asked to remove you, not giving the treatment a chance! Or Doctor Bottle’s reputation, either!”

I Cannot Eat

“Drat Doctor Bottle and her reputation!”

“Quite so, but your people? They have made sacrifices. You can’t let them down, and there is always the chance you might infect someone at home, besides making life uncomfortable for them—open windows, special food!”

Every Saturday Mrs. Cranleigh dined with us. She came from a distance to visit her son and her daughter. Both were patients in the San. The son was bad, the daughter only slightly infected. Mrs. Cranleigh had already lost two children with T.B. She was taking no chances with Kate.

In spite of her children that were dead and her children that were sick Mrs. Cranleigh was hideously buoyant and optimistic. The staff alluded to her as “that brave soul!” They said she was a “moral uplift” to the San. She paraded her fortitude to such an extent and hoisted her buoyancy to such a pinnacle it made everyone else slump.

Dr. Sally Bottle

Good Friday Morning. Doctor in bed eating hot cross buns.

Mrs. Cranleigh’s favourite food was cabbage. The San garden excelled in great crisp monsters; all of the cabbage tribe were represented. Miss Brown, the gardener, Doctor Bottle who was always present at Saturday’s dinner, and Mrs. Cranleigh lapped up the flabby green with relish, discoursing all through the meal on the merits of the different species. Mrs. Cranleigh kept up a running undertone, “Beautiful cabbage! Beautiful cabbage!” The patients nicknamed her, ‘Beautiful Cabbage’.

Then Doctor Bottle would insist that everyone must have a second helping. She inflated over the San’s beautiful cabbage, till she nearly burst. It was a privilege to be able to eat home-grown cabbage such as this! “Beautiful cabbage. Beautiful cabbage!” echoed Mrs. Cranleigh till we hated cabbage of every kind, human or vegetable.

Marmaduke Jepson sat near the dining-room door; he always sprang from his seat to open it for Doctor McNair. When she swept from the head of the table down the long dining-hall, Dr. McNair, what with her great height, the flowing dinner gowns she always effected, and all the dignity she had at her command, looked like a ship in full sail advancing.

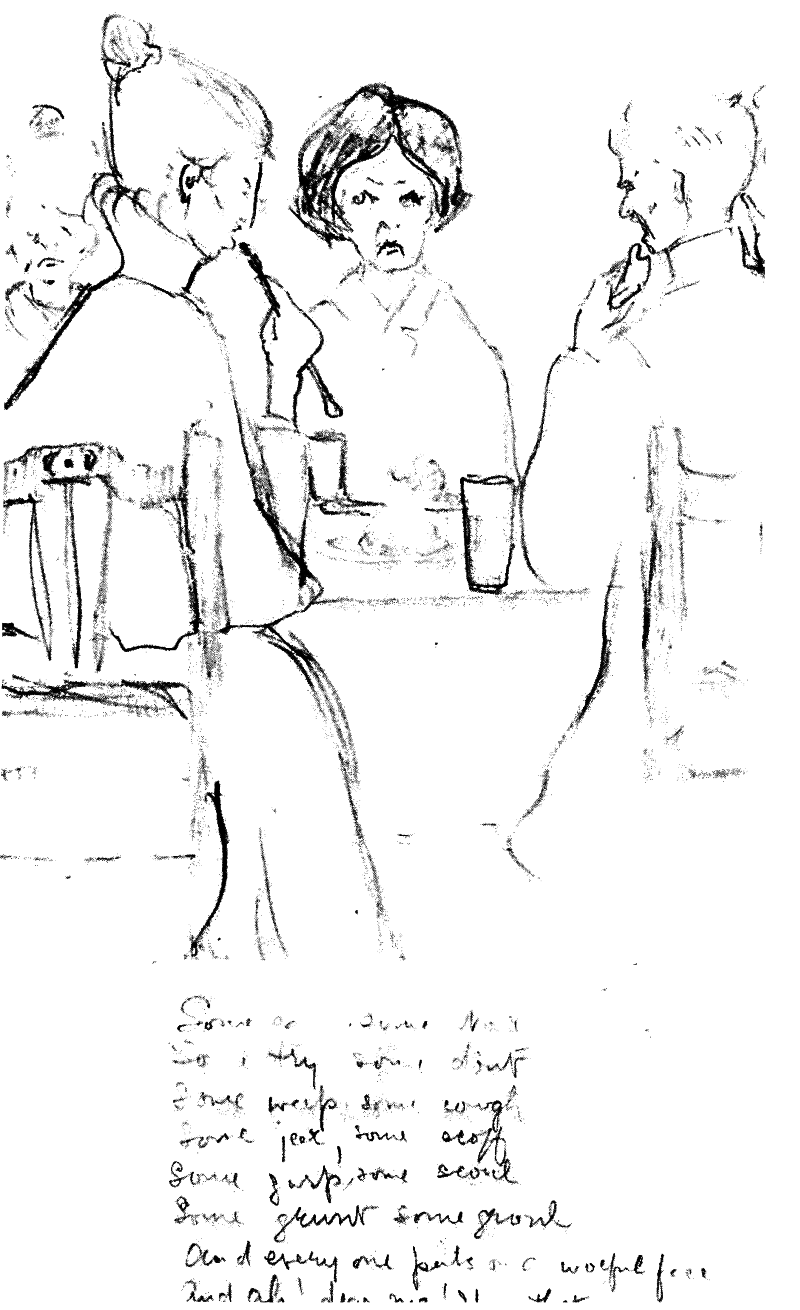

Some eat, some won’t,

Some fry, some don’t,

Some weep, some cough,

Some jeer, some scoff,

Some gasp, some scowl,

Some grunt, some growl,

And everyone puts on a woeful face

And ah! dear me! I fear that none say grace.

Some Eat, Some Won’t

Marmaduke sprang as usual, took out a perfumed florid handkerchief with a flourish, fluttered it to undo its folds, pulled out more than the handkerchief. Plop! Right in front of Doctor’s feet slapped the pancake Marmaduke should have eaten at table. Doctor had to detour to avoid treading on it. Marmaduke swooped—too late! The Doctor swept by with a pointed, “See you at Rest Hour, Mr. Jepson.”

“Good Lord, Dane!” Marmaduke called to the spinach objector, “did you see her face? Quick, let’s make a prompt get-away for our walk.” They took hats and sticks from the hall-rack and bolted.

“One minute, Dane.”

Jepson took his cane and bored a hole in the soil of the garden, widening and deepening the bore to accommodate the pancake and an envelope, very fat. Carefully he covered them with earth.

The lady gardeners could have told of a vast undercrop of envelopes addressed to Marmaduke Jepson, Esq. in the garden. They did not. Marmaduke always had a smile for them, always a compliment.

0 comments