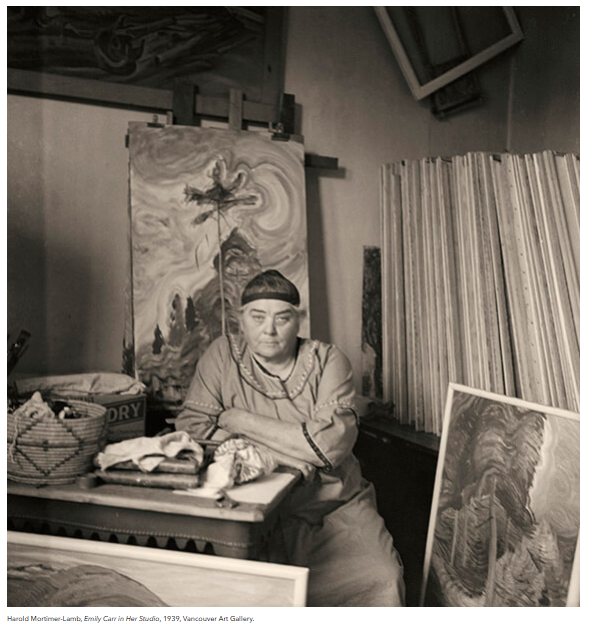

Few artists impact the world equally with their paintings and paragraphs. Van Gogh was one, Emily Carr (1871–1945) another, and she was one of the first Canadian artists of national significance to emerge from the West Coast. During her life she felt her artistic career was a failure. Saddled with a sense of professional and personal isolation and rejection, she persevered and her vision of Canada is now iconic.

Carr travelled extensively, learning from European, American, and indigenous forms and receiving formal training at art academies as well as with private tutors. She continued to grow in artistic power throughout her life as a result of her own intense observation and of her vigorous experimentation with a variety of methods and media, reflecting the fusion of wide-ranging influences.

Emily Carr is one of Canada’s best-known artists. Her life and work reflect a profound commitment to the land and peoples she knew and loved. Her sensitive evocations reveal an artist grappling with the spiritual questions that the Canadian landscape and culture inspired in her.

Her early years

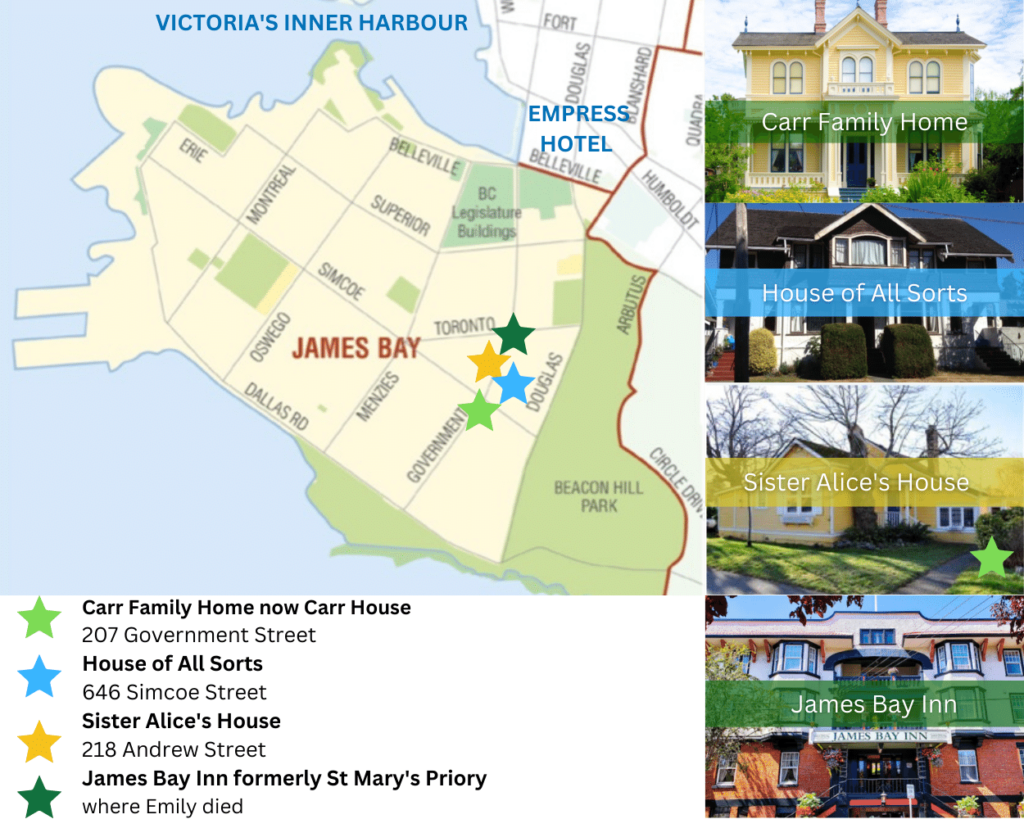

Emily Carr was born on December 13, 1871, in Victoria, B.C. She was the second youngest in a family of nine children, with four older sisters and four brothers, only one of whom, Dick, lived to adulthood. Her father, Richard Carr, was born in Crayford, Kent, England, and had travelled in Europe, the Americas, and the Caribbean in search of a place where his entrepreneurial ventures could flourish.

Richard returned to England briefly with his wife, Emily Saunders, to enjoy the wealth he had accumulated as a merchant in California, before moving permanently to Victoria in 1863. The city was an expatriate British settlement, home to the Songhees First Nation and a significant population of Chinese workers and merchants. About her father Carr writes,

As far back as I can remember[,] Father’s place was all made and in order. The house was large and well-built, of California redwood, the garden prim and carefully tended. Everything about it was extremely English. It was as though Father had buried a tremendous homesickness in this new soil and it had rooted and sprung up English. There were hawthorn hedges, primrose banks and cow pastures with shrubberies…. Just one of Father’s fields was left Canadian. It was a piece of land which he bought later when Canada had made Father and Mother love her, and at the end of fifty years, we still called that piece of ground “the new field.”

Emily Carr

Richard Carr was a key influence on the young Emily: while proud of his English heritage, according to her, he desired a “Canadian education” for his family. He sent his daughters to public schools rather than the private finishing schools that were regarded as the proper education for young middle-class Victorian girls.

His gift to Emily on her eleventh birthday was The Boy’s Own Book of Natural History, and he encouraged her independence and spirit. At the same time his authoritarianism and sternness led to her early sense of alienation and rebellion—a self-identification she never abandoned and one she depicted regularly in the books and journals she produced throughout her life.

Study in California and England

Carr’s mother, to whom she was very close, died of tuberculosis when Carr was fourteen. When her father passed away two years later, the family was left in the care of the eldest daughter, Edith. Unable to tolerate her sister’s strictness, Carr persuaded her guardian, James Lawson, to allow her to study art at the California School of Design, in San Francisco, beginning in 1890. After three years she was forced to return to Victoria because of dwindling family resources.

She began teaching art classes in her studio, and once she had sufficient savings, she embarked in 1899 on her second study sojourn, at the Westminster School of Art in London, England. Disappointed with its conservative instruction and the squalid conditions in London, she left the school after two years.

In 1901 Carr went to Paris for twelve days, where she visited the Louvre several times as well as private galleries. In the spring of that year she might have seen works by Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Fauve artists, including Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Claude Monet (1840–1926), Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), and Henri Matisse (1869–1954), among others. This short trip convinced her that Paris was a greater centre for art than London.

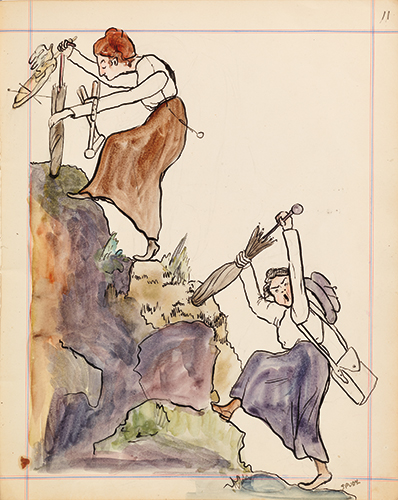

Later that same year she went to St. Ives, an artists’ colony and fishing village in Cornwall, recommended to her by a classmate in London. There she joined the Porthmeor Studios, under the tutelage of Julius Olsson (1864–1942) and his assistant Algernon Talmage. Carr left St. Ives after eight months and attended Meadows Studio at Bushey, Hertfordshire, where she studied under John Whiteley.

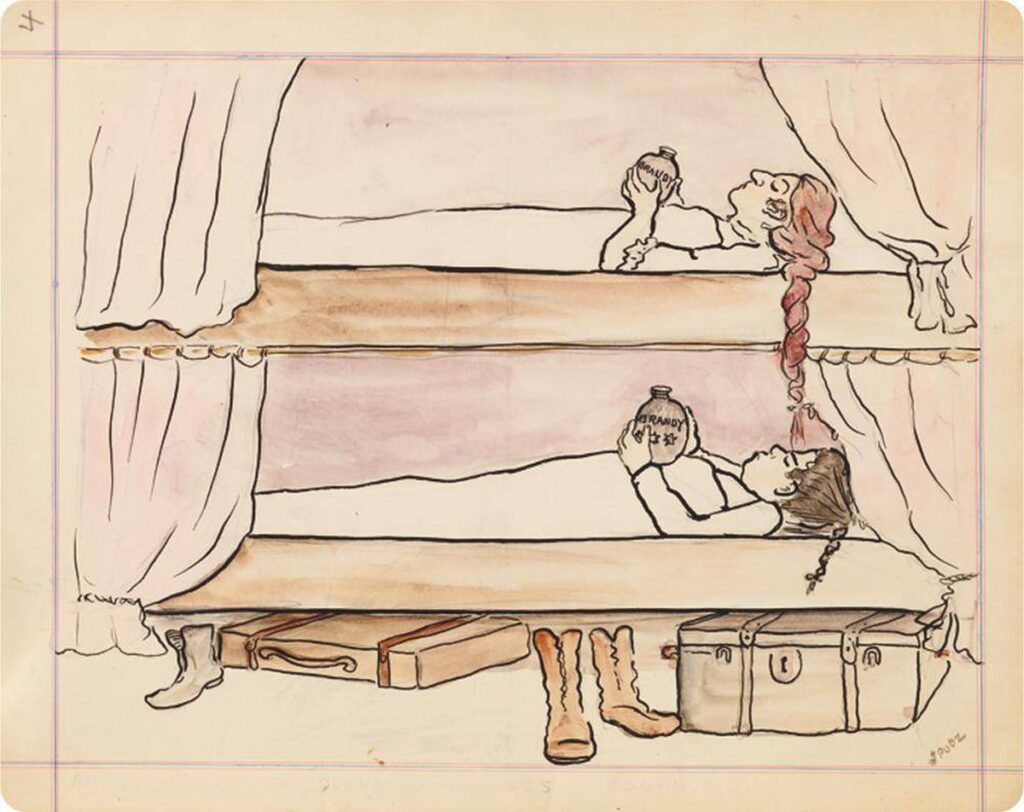

Back in London Carr suffered from continued illness and a growing sense of displacement. One of her sisters was summoned from Canada after Carr did not respond to the ministrations of her wealthy Belgravia friends. In 1903 she was hospitalized at the East Anglian Sanatorium, where she stayed for the next eighteen months, diagnosed with hysteria. Her highly regimented treatment at the clinic, designed for TB patients, made it impossible for her to paint, though she did create a series of drawings, later published as Pause: A Sketch Book, documenting her stay there. After her release she made a brief sketching trip to Bushey before returning home to Canada in 1904.

Return to Canada

Carr returned to the West Coast by way of Toronto and the Cariboo region of B.C. and began teaching in Vancouver. She was discouraged by what she perceived as her failure in London. At first her pupils were society women at the Vancouver Studio Club and School of Art, and she became frustrated by their lack of artistic commitment. She then opened her own art school for children, which was highly successful.

In 1907 she and her sister Alice took a sightseeing trip to Alaska. Carr chronicled their adventures extensively in her notebook and in sketches, documenting everything they experienced, from extreme seasickness to visits to Sitka’s totem poles. The trip was to have a profound influence on Carr, who began to imagine a new project, one that would occupy the next five years of her life: documenting the Aboriginal village sites in British Columbia.

France 1910 – 1911

In 1910 Carr once again travelled abroad for study, this time to Paris. She stayed for fifteen months, and the technical and stylistic training she experienced in France changed her work irrevocably. As in England she quickly tired of the large city. “I could not stand the airlessness of the life rooms for long,” she writes later, “the doctors stating, as they had done in London[,] that ‘there was something about these big cities that these Canadians from their big spaces couldn’t stand, it was like putting a pine tree in a pot.

She retreated to a spa in Sweden for several months, returning to study with Harry Phelan Gibb (1870–1948) in Crécy-en-Brie, east of Paris, and in Brittany. When Carr studied with Gibb, he was painting in the Fauvist style.

Despite these interruptions her work flourished. The French paintings—including Brittany, France and Breton Farm Yard, both c. 1911—reflect a new boldness, and in 1911 two of her paintings were accepted for exhibition at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. Her fellow Canadian James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924) and her teacher John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961) were also represented there, along with Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Matisse, Francis Picabia (1879–1953), Georges Rouault (1871–1958), and Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940), among others.

When Carr returned home in 1912 she organized an exhibition in her studio of seventy watercolours and oils from the French sojourn—she was the first to introduce Fauvism to Vancouver.

Early First Nations Work and Hiatus. 1912 – 27

On her return Carr initiated her documentation project with renewed vigour, embarking on the most extensive excursion she had ever taken in British Columbia. She travelled to the islands of the Northwest Coast, including Haida Gwaii, as well as to the Upper Skeena River,

Whenever I could afford it I went up North, among the Indians and the woods, and forgot all about everything in the joy of those lonely, wonderful places. I decided to try and make as good a representative collection of those old villages and wonderful totem poles as I could, for the love of the people and the love of the places and the love of the art; whether anybody liked them or not…. I painted them to please myself in my own way, but I also stuck rigidly to the facts because I knew I was painting history.

Emily Carr

In 1913 she organized an exhibition of two hundred works from this period at the Dominion Hall in Vancouver. It was her most ambitious project, and one that represented the culmination of five years of work—it was also the largest solo exhibition mounted by an artist in Vancouver at that time.

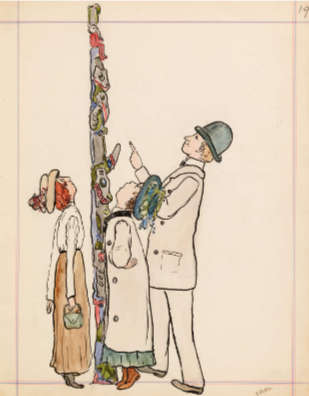

At Dominion Hall she delivered a talk, “Lecture on Totems,” in which she described—within the colonial perspective of the day—her understanding of indigenous cultures, declaring finally, “I glory in our wonderful west and I hope to leave behind me some of the relics of its first primitive greatness. These things should be to us Canadians what the ancient Briton’s relics are to the English. Only a few more years and they will be gone forever into silent nothingness and I would gather my collection together before they are forever past.

In contrast to her lecture, her work from this period shows a living culture: peopled villages alongside longhouses and totems. The communities she depicts were as much a part of her vision as the cultural objects she found there. Carr tackled her project energetically and wrote to the minister of education in British Columbia to request his support, stating, “The object of my work is to get the totem poles in their own original settings. The Indians do not make them now and they will soon be a thing of the past. I consider them real Art treasures of a passing race.”

Unfortunately, the reviews of her exhibition were mixed, and when she offered the paintings to the new provincial museum they were refused—their daring modern execution was thought not to accurately represent the totem poles and villages she had so assidously been recording.

At home in Victoria she produced hooked rugs and later pottery on which she incorporated First Nations iconography for the tourist trade, but she ultimately felt that this was a form of exploitation of Native motifs. With the exception of her early art studies in San Francisco, London, and Paris, Carr had been isolated, in collegial terms, on the West Coast of Canada among conservative relatives, middle-class society, and primarily academic painters.

Her creative and intellectual inspirations were unconventional, as seen in her espousal of European modernism and her fascination with First Nations cultures, and her extensive journeys to indigenous villages throughout the southern interior and coastal areas of British Columbia.

From the late 1920s she also sought enlightenment from First Nations culture, extensive journeys to indigenous villages throughout the southern interior and coastal areas of British Columbia, Hindu priests, expatriate Chinese artists, and humanist philosophers and writers whose mysticism helped her to navigate her responses to nature—Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, in particular. But from 1913 until 1924, when she began a fruitful association with Seattle artists, particularly Mark Tobey (1890–1976), she had felt her artistic career was a failure.

Success and Recognition, 1927 – 1945

Perhaps because of her ongoing sense of professional and personal isolation and rejection, Carr chose her associations carefully. She writes, “That is one thing about people I put in my garden down in my heart. I have noticed that I do not remember their outside appearance, but their inside looks only. I forget their features. I think that is my test whether they belong to the garden, because it is a garden for souls, not for outsides.”10

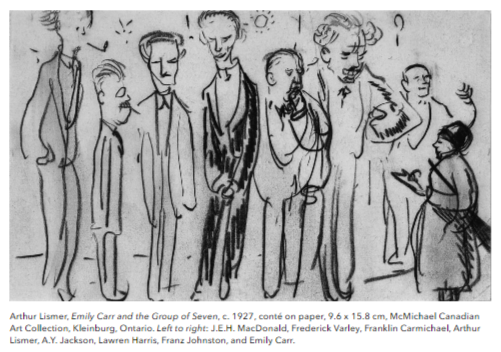

Carr’s national recognition came only in 1927, when she was in her fifties. Eric Brown, the director of the National Gallery of Canada, visited her and invited her to join the Group of Seven in a major show he was organizing in Ottawa, Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern. Her work had been recommended to him by Marius Barbeau, the ethnologist at the National Museum of Canada and co-curator of the show.

Twenty-six of her oil paintings— including Tanoo, Q.C.I., 1913—as well as pottery and hooked rugs, were selected for exhibition. Brown also recommended a book, A Canadian Art Movement: The Story of the Group of Seven by Frederick Housser, which introduced her to the work of the artists. As she travelled to Ottawa, Carr stopped in Vancouver to meet F.H. Varley (1881–1969) and in Toronto where, over several days, she met with Lawren Harris (1885–1970), Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), all members of the Group of Seven, who welcomed her into their studios. At the conclusion of the visit Harris told her, “You are one of us.”11

His words were particularly important to Carr, who had so little positive critical or collegial response to her art until this point. Harris would quickly become an important mentor to Carr. Of all the group’s work, Harris’s touched her the most:

Always, something in it speaks to me, something in his big tranquil spaces filled with light and serenity. I feel as though I could get right into them, the spirit of me not the body. There is a holiness about them, something you can’t describe but just feel.

The trip was transformational; Carr met many of the central figures working within modernism in Anglo Canada, the new affiliations ending her long professional estrangement. That event marked a turning point in her career: thereafter she entered a mature period in which she produced the work that would gain her national and international recognition—such as Zunoqua of the Cat Village, 1931—and greater respect in British Columbia, though the modernity inherent in her paintings continued to make them unpopular in Victoria during her lifetime.

Carr was invited to exhibit with the Group of Seven in 1930 and in 1931, and after they disbanded she joined the Canadian Group of Painters. These connections, and especially her friendship with Lawren Harris, were a continuing stimulus, as was a 1930 trip to New York, where she was introduced to Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986). The young B.C. painter Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) and a Chinese artist in Victoria, Lee Nam, were fruitful local contacts.

Although she would remain in Victoria and at a distance, these connections sustained her for the rest of her career. The inclusion of her work in group exhibitions at the Tate Gallery in London in 1938 and at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, however, marked her entry onto the national and international stage.

Her Writing Life

After 1937, when Carr’s health made painting difficult for her, she turned mainly to writing, producing a series of books. The stories she wrote reflected on her life and times and brought her praise and recognition. In 1941 she won a Governor General’s Literary Award for her first book, Klee Wyck, a collection of twenty-one stories about her travels to coastal villages. Other story collections published during this time explored her childhood (The Book of Small, 1942) and her years running a boarding house in Victoria (House of All Sorts, 1944).

Carr suffered a severe heart attack in 1937; she died in Victoria in 1945. Just before her death Carr learned that the University of British Columbia had decided to award her an Honorary Doctor of Letters. Seven years later she represented Canada posthumously in its first participation at the Venice Biennale, along with David Milne (1882–1953), Alfred Pellan (1906–1988), and Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974).

Ira Dilworth, a friend and the executor of her estate, continued to publish her writings: first her autobiography, Growing Pains, in 1946, and, in 1953, two further volumes: The Heart of a Peacock, a book of recollections and fictional stories that he organized from the papers left to him; and Pause: A Sketch Book. Carr’s personal journals, Hundreds and Thousands, documenting her later professional and artistic development, travels, and friendships, were published in 1966.

from: Emily Carr: Life & Work by Lisa Baldissera for Art Canada Institute

Lisa Baldissera has worked in curatorial roles for public art galleries in western Canada and as an independent curator, consultant, and writer for nearly twenty years. She was curator of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and chief curator at the Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, and is currently senior curator at Contemporary Calgary. She has produced more than fifty exhibitions of local, Canadian, and international artists. She holds MFAs in creative writing from the University of British Columbia and in art from the University of Saskatchewan and is currently a PhD candidate at Goldsmiths, University of London. Baldissera was a Professional Affiliate at the University of Saskatchewan and has served on contemporary-art juries across Canada, including for the RBC Canadian Painting Competition, the Sobey Art Award, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, The Hnatyshyn Foundation, and the British Columbia Arts Council.

Emily spent most of her life in the James Bay Neighbourhood

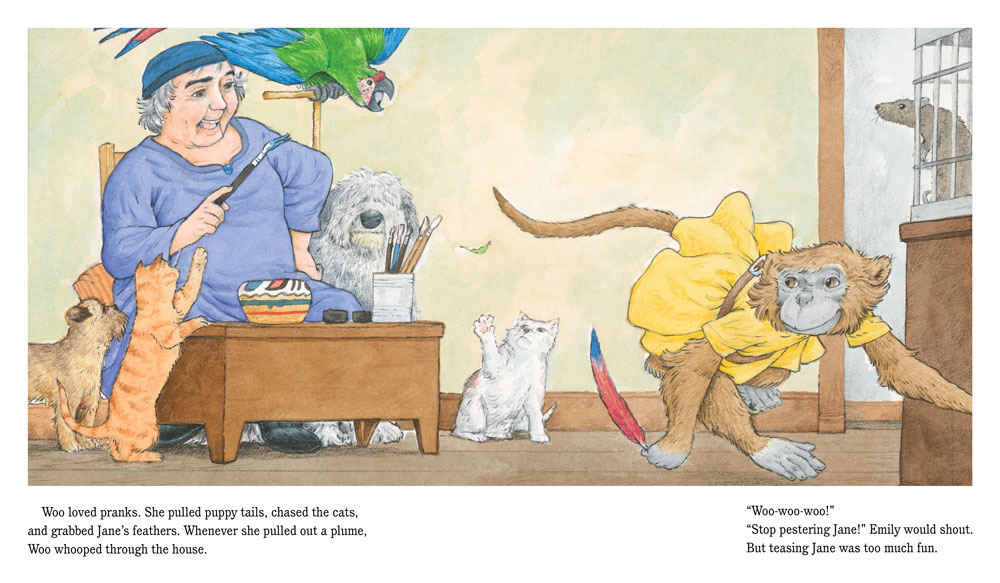

Emily loved her furry friends