Christmas descended upon the San as an enormous ache, a regular carbuncle of homesickness with half a dozen heads.

A super-cheerful staff festooned greenery on Christmas Eve. Overworked stomachs groaned at the enormity of Mrs. Green’s preparations.

The post-bag went out from the San stuffed with the gayest of Christmasy letters written by patients practically drowning in tears. Beside each bed was a little pile of cards addressed to various comrades in exile. Nurses would deliver them on breakfast trays, jokey nurses lit with fraudulent gaiety—tainted exiles, nevertheless, homesick as the rest of us.

Hokey, gathering my Christmas cards, caught her breath, dumped the pile hastily from chair to apron pocket, left the room. I tried to remember whose name was on the top of my pile, the name that choked Hokey. For the moment I could not. A horrible noise began out on the terrace. Four men and two boys came reeling past our rooms, singing a carol in six different keys, peering impertinently into the lighted rooms. Everyone switched into darkness, became headless bumps in beds.

While the boys screeched a duet, the four men paraded up and down the terrace, thrusting a tin cup into the rooms at arms’ length, rattling a penny to the tuneless jumble of tipsy whimpering. “ ’Ave a ’eart for the poor Waits. What for the Waits?” Between each shake of the cup the men whined. Receiving no response the Waits grew angry, insulting. They had been drinking. They stood on the terrace silhouetted against the night, refusing to go till they got money.

Nurses took the tin cups and carried them from room to room. Everyone was angry at hearing the dear old carols insulted on drunken tongues. A few pennies clanked into the cups to induce the Waits to go. Religious little Jenny I could hear crying through the wall. Susie Spinner on the other side of me was shouting one of her tiresome jokes to Hokey through the open transom.

Christmas day broke dark and windy with little flurries of snow. The big dinner was set for five, with a light lunch at noon when every patient was permitted to eat as much or as little as he wished. All patients that could sit up were dragged to the festival table. If they could not walk they were taken in wheel-chairs. Complete “Downs” were served decorated trays in bed.

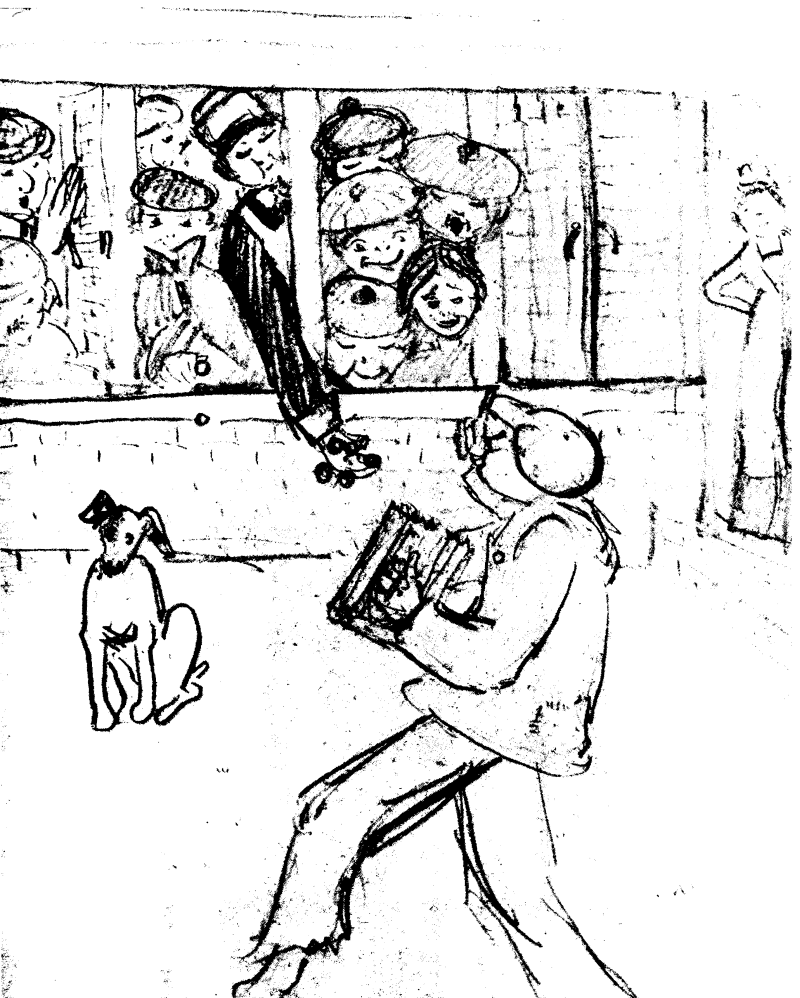

Concertina

April 10

Enormous excitement in the San. Boy with concertina arrives. Pennies scattered in all directions. Large percentage of high temperatures that night.

Log fires burned in the grates at either end of the long dining-hall. The corridors smelled of pine boughs, holly prickled in corners, mistletoe was taboo. (T.B.’s are not supposed to kiss.) Scarlet-dressed maids flittered about like robins. Through the steamy kitchen Mrs. Green’s voice boomed like a deep sea liner in a fog.

We wore our usual woolly garments with a sprig of holly stuck on us somewhere. Monster turkeys, juicy and rosy brown, were dismembered at the side-table by Doctor Mack and Matron. The turkey helpings were heaped about with sauces and dressings. The pudding burned with brandy-fire. The sprig of holly on top crackled. At the end of the meal, toasts were drunk in a pink liquid, non-alcoholic. All plates were emptied because they did not have to be and because it was a splendid dinner. Mrs. Green was called for. They pulled her into the dining-room, scarlet with embarrassment, little trickles of sweat meandering down her cheeks. She dare not mop for fear of slopping the pinkish liquid in her glass. She just got redder and redder, bracing herself against the swing door. It took several maids to keep the door taut.

“Mrs. Green! Hurrah!” All solemnly drank.

“Speech, Mrs. Green! Speech! Speech!”

It was not possible for her red to go redder. Her hand shook so violently she had to entrust the pink liquid to a maid. Mrs. Green’s kind blue eyes embraced us every one. She burst out with ill-suppressed sobbing.

“Pour souls! Poor souls! God bless youse all!” Then completely overcome she ordered the maids to give way and let her back into her kitchen.

Chairs shuffled; we moved into the sitting end of the dining-hall for entertainment. Gathered around a real fire, comfortable, we were strangers to each other. In the open, taking treatment, at table struggling with food, we were comrades, intimates; sitting cosy, warm, luxurious, we were strangers.

Lung patients turned faint from unusual warmth and were compelled to move to the open windows; sitting quietly there, they watched the falling snow.

A Christmas paper had been preparing for several weeks. Every San patient had contributed something. It was to be read aloud on Christmas night.

The Reverend Brocklebee put on his spectacles, moved up under the light, cleared his throat, spread the paper.

My contribution was called, “Matron’s Dream”. It was a skit on the names of all patients and staff in the San. In the middle of my very best sentence the Reverend Brocklebee stumbled, peered close, reddened, skipped.

Fool! What a mess he had made of it! Couldn’t the man read? Or had some name been purposely omitted? Miss Ecton had not been at the dinner-table. She was up and about yesterday. I remembered Hokey’s face as she pocketed my cards. Miss Ecton’s name had been on top. Now I remembered. It was the last card to be addressed.

We did not have a Christmas tree but there was gift-giving of sorts. Skeletons of dressing screens without their drapery were placed at one end of the room. On these hung a multitude of little butcherish brown paper parcels (each might have contained one chop). The parcels were knotted and tied with white butcher-string. Each patient was blindfolded, led to the rack, to choose his own parcel, silly little gifts aimed to provoke a smile. The San meant well.

When we had all taken, each nurse stepped up and took for her bed patients.

“Hokey, you forgot Miss Ecton.” I watched her closely. There was sham behind her casual, “So I did,” and stepping jauntily she took another parcel. Hokey couldn’t act well.

At nine o’clock we went to our rooms. Christmas was done, and nobody was sorry.

Hokey came to tuck me up. “Hokey, I know. You need not lie. Tell me about Evelyn Ecton. I chatted with her last night at five o’clock on the porch.”

“She was dead at six—haemorrhage,” Hokey choked.

Evelyn Ecton had come to the San about the same time as myself. We both were Hokey’s patients.

Yesterday I had appeared on the porch, first time up in two months. Evelyn Ecton coming back from her walk greeted me, “Hello, I’ve been up, you down. See-saw, see-saw.” She laughed. All Christmas Day she had lain in the San morgue awaiting burial. We Christmased within earshot of the little brick morgue but Evelyn Ecton’s self was away. Our forced merriment did not disturb her rest.

0 comments